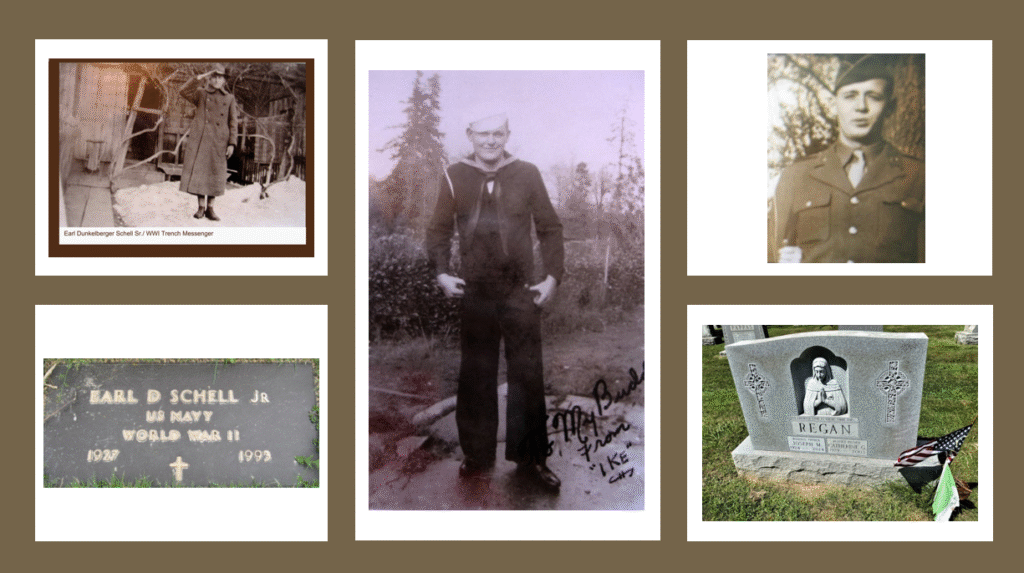

This next stop hits close to home as we approach Memorial Day and take time to remember those who gave it their all in service to our nation. Imagine being a combat veteran, requesting your military records for proof to secure a plot in a national cemetery, and being denied? This is the battle some of our veterans are facing today – and it’s because of a fire.

While in St. Louis for the Fire Equipment Manufacturers’ Association meeting, I stumbled upon the National Personnel Records Center (NPRC). This center was and continues to be the largest repository of military service records in the country. Sadly, this facility suffered a multiple-day fire in July of 1973 and is considered the worst archival disaster in American History. The impact of this fire is still ever-present today, as some of our oldest veterans request their military records for benefits and burial services and are told there are no records to prove their service. As the Granddaughter of two veterans who did make it home, and had military funeral honors, this story has a personal impact.

While no one knows for sure what started the fire on July 12, 1973, the destruction is clear. Approximately 16-18 million official military personnel files for Army discharged between November 1912 and January 1960, as well as Air Force personnel discharged from September 1947 to January 1964, with surnames starting with the letters “I” through “Z,” were lost due to the fire.

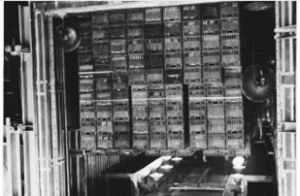

Originally, the NPRC was occupied by the Army for storage of records in metal cabinets. Later, the Navy occupied part of the first and second floors for storage or records on open steel shelving. In 1960, the General Services Administration (GSA) took control of the building, and the storage of records was changed to cardboard boxes on steel shelving. While many owners are not aware of the impact that operational and physical changes can have on fire protection systems, such as changing storage containers from metal cabinets to cardboard boxes, NFPA 25, Standard for the Inspection, Testing, and Maintenance of Water-Based Fire Protection Systems, provides an Owner’s Questionnaire designed to assist the owner in identifying whether any changes have occurred that could impact the capability of the fire protection system to control a fire. This questionnaire could be given to owners by insurance representatives or Inspection, Testing, Maintenance (ITM) service providers at annual inspections to assist the owner in maintaining the effectiveness of their systems.

The six-story building, which is larger than three football fields or several city blocks, was constructed of reinforced concrete. When the fire started, the records were stored on 9 ft. shelves, 2-1/2 ft. deep, back-to-back (so really 5ft deep) with aisles widths of 29 in., and a 12 ft. high ceiling. Sprinklers were installed on the first and second story only. The building had wet standpipe systems installed.

At the time, the fire verified the position stated in NFPA 232AM, Manual for Fire Protection for Archives and Records Centers, which essentially stated that the protection of mass collections of records necessitates either storage in totally enclosed steel containers or protection by a fully capable automatic extinguishment system. Sprinkler protection was recommended when GSA assumed control of the building, and plans were underway to provide total sprinkler protection for the facility. Due to a lack of funding, sprinklers were not installed throughout the facility. In the aftermath of the fire, an emergency request for repairs, including funds to install a sprinkler system, was approved by Congress.

Numbers 3 and 4 of Volume 68 of the 1974 NFPA Fire Journal Articles discuss the NPRC fire and record recovery methods in greater detail. The summer climate in Missouri, with high temperatures and humidity, created the perfect climate for mold to grow. Some of the methods to save records included the use of Thymol to control mold and mildew, Borax to absorb moisture, and the most used recovery method: the vacuum drying process. In this method, records were placed in plastic milk containers on open racks and loaded into a humidity and temperature-controlled chamber. The ambient temperature and air were evacuated until the temperature in the chamber was freezing. Then, the chamber was purged with hot, dry air until the records were warmed to 50⁰F. Over 2,000 milk containers – which each contained approximately 8 lbs of water – were removed from each case, which in turn was nearly 8 tons of water for each cycle in the chamber. This process was conducted at a NASA facility and at McDonnell Douglas Aircraft Corporation.

showing plastic cartons of records, National Archives and Records Service, NFPA Journal

Once the records were dried and returned to NPRC, the records were entered into a new computer-based index named “B” registry. In 2011, the New NPRC completed construction of its new facility, which was built for long-term record storage with improvements for storage design, including separation into smaller storage areas to prevent massive fire spread, climate-controlled bays, early-warning smoke detection systems, a robust fire suppression system, and emergency response plans that are updated annually.

If your records were destroyed in the fire, the VA requests you follow these steps.

“Freedom makes a huge requirement of every human being. With freedom comes responsibility.”

— Eleanor Roosevelt